Rick White

Paradise Guard Station Artist-in-Residence

July 6-27

Bitterroot National Forest

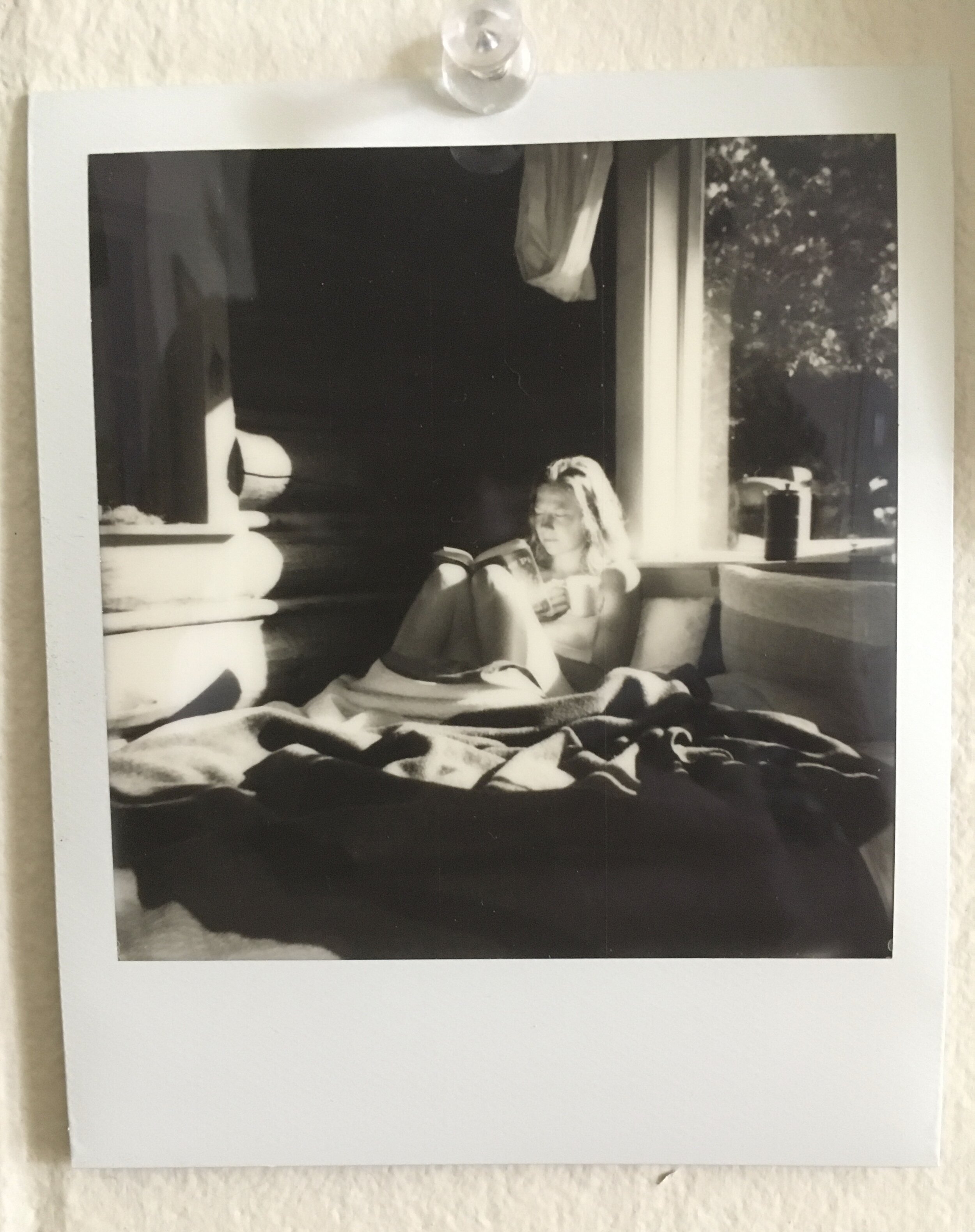

The view from Monica’s corner of Paradise

I was walking along the Missoula river trail on a chilly April morning when I got the call from Stoney Samsoe of Open AIR, letting me know I’d been selected for an artist residency in July. Thanks to COVID-19, I had been out of work for nearly a month. My girlfriend Monica and her dog Jude lived thirteen-hundred miles east in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. We were awaiting news on my applications to graduate school programs to see where — or if — we’d finally be relocating to be together in the same town. The long walks I took with my hound dog Finn were then my only connection to the world outside my apartment; at least, they were my only connection not mediated by a phone line or computer screen. Finn and I meandered in midday, between mornings of reading and writing and evenings of cooking soup enough to survive the apocalypse. Social distance, isolation, and quarantine were just entering the common vocabulary. To me they felt like coats I’d been wearing all winter long. Then Stoney called and offered me the residency: three weeks off-grid in the heart of the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness to focus on my writing. I hesitated. Was more solitude really what I would be needing come July? More disconnection from society? More social distance? More isolation?

Social distance

The answer: absolutely…but only if Monica and the dogs could join me. Thanks to Stoney at Open AIR, to Krissy Ferriter at SBFC, and to Erica Strayer and others at the USFS, they did join me, and our three weeks at the Paradise Guard Station this summer were some of the best weeks of our lives.

On the afternoon of July 6th, Tanya Neidhart welcomed us to Paradise and gave us the rundown: how to keep the water tank filled; how to use the radio and the InReach to check in with dispatch; how to use the propane fridge; where to watch for rattlesnakes. We unpacked our food, books, and clothes. We ate a quick sandwich and some chips for supper. Then, after a sunset stroll down to the Selway River boat launch with the dogs, we lit a red candle on the window ledge above the bed, watched the big moon rise over an unfamiliar ridge, and slept.

Playing

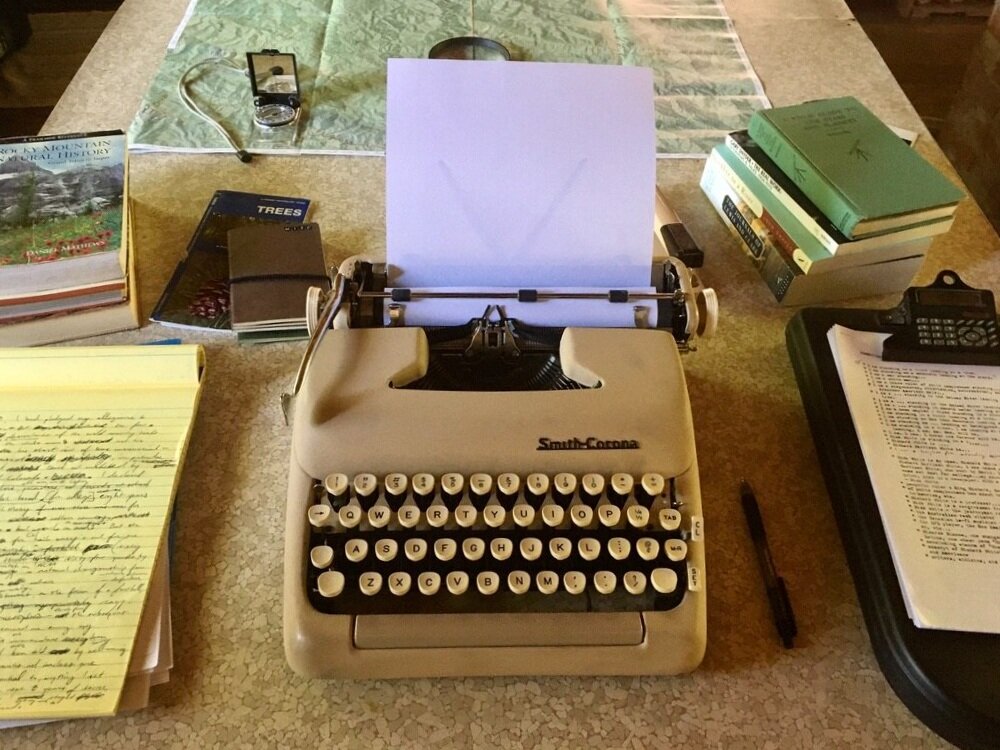

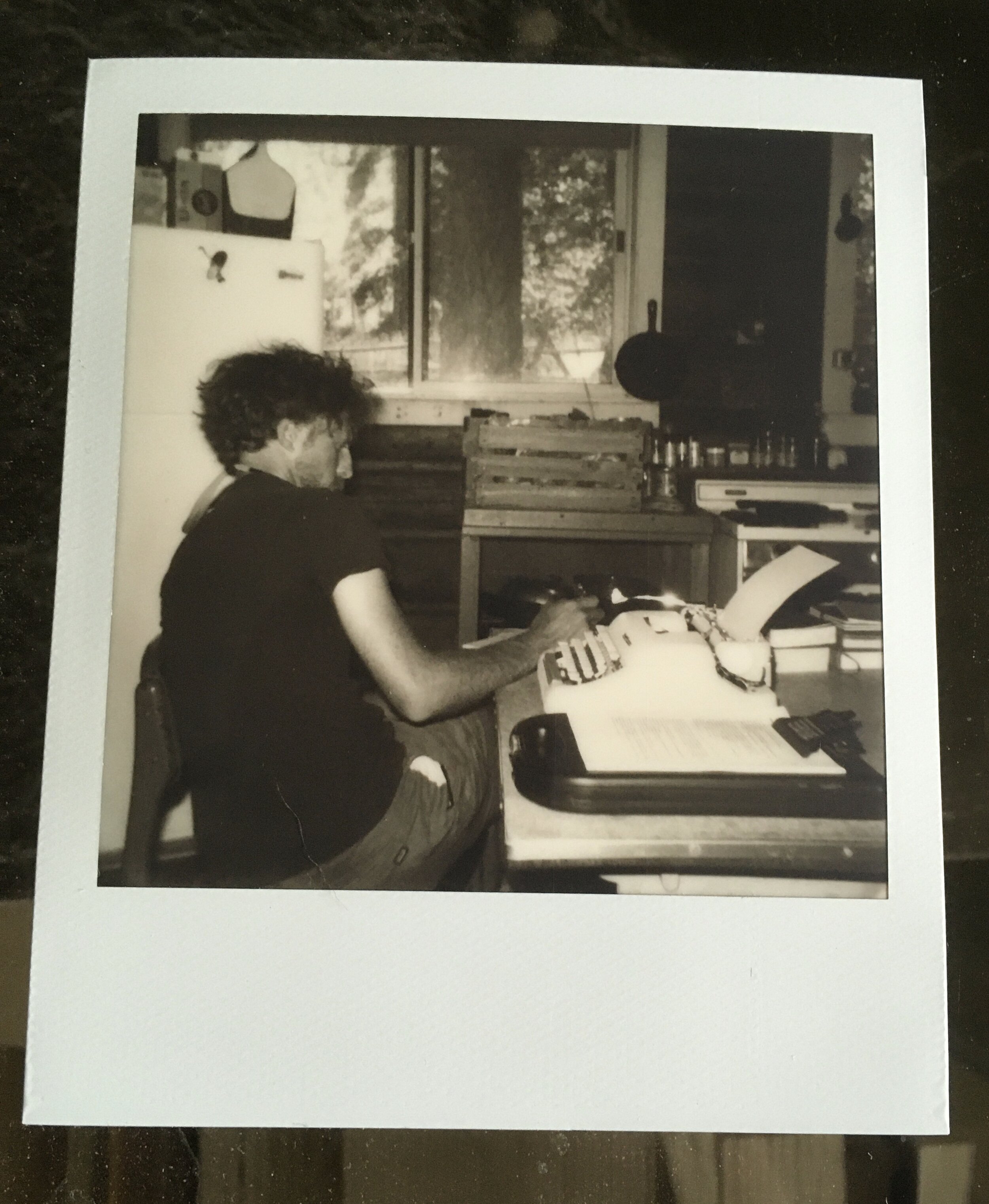

We slept hard. Months of constant calibration to coronavirus curves, stock market fluctuations, and unemployment application numbers had taken its toll. The relief was astounding. Time in Paradise was suddenly, wonderfully measured not by the hours until the next COVID press conference, or even by the hands on a clock, but by the arc of the sun in the sky, by the length of shadows. Three weeks felt like three years. Also like three minutes. Each day was wonderfully similar. I woke early, made coffee, and wrote in my journal. Monica read, walked the dogs, and cooked breakfast. I wrote essays on yellow legal pads in the late morning, typed them up on my 1957 Smith-Corona in the afternoon, then went fishing. Monica took hikes up White Cap Creek or down the Selway, or relaxed with a book by the creek. I kept the campground weedeated and the toilets cleaned and stocked with toilet paper. We checked in with river groups preparing to launch. Chatted with campers. We cooked dinner, built campfires. I picked on a travel guitar for half an hour or so each night, then the sun set, the moon rose, and we slept, and slept hard.

The dreaded blank page

Even more than time to write or a quiet place to write, every serious writer needs routine. At least, I do anyway. Fortunately, thanks to Open AIR, the Forest Service, and SBFC, this summer I had all three. I wrote more in those three weeks than I did in the entire year leading up to the residency. What’s more, Monica and I became deeply connected to one small chunk of an immense wilderness, and now feel like characters (however minor) in the story of that wilderness, and members of the team of stewards committed to protecting that wilderness and using it well. We miss being in Paradise. More than that, though, we feel grateful for the time we had together there, grateful for all the good people we worked with and met, and excited to do our part to make opportunities like this possible for others in the future.